Director’s Message

Valley Fever Center for Excellence

November 2025

Welcome to the Valley Fever Center for Excellence. At the Center, we try to provide reliable and timely information about coccidioidomycosis, the medical name for Valley fever.

In 2003, the Valley Fever Center for Excellence (VFCE) designated a week in November as Valley Fever Awareness Week, and more recently this tradition has continued in partnership with the Arizona Department of Health Services (AzDHS). This year, November 8th through 16th has been designated as the time to focus attention on this problem so important to the health and the economy of Arizonans. There are several events which can be found here. One in particular is a webinar for clinicians and the public entitled “Managing Valley Fever for Arizonans. It All Starts with Awareness.” The importance of that single word, AWARENESS, is what I would like to expand upon now.

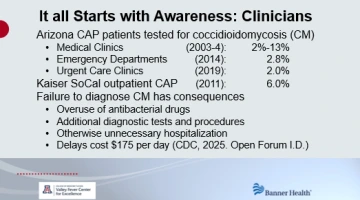

With approximately two-thirds of all Valley fever infections in the United States occurring in Arizona, it is reasonable to assume that physicians and the community at large here would be aware of this disease. Surprisingly and repeatedly documented, this does not turn out to be the case. Valley fever is often the cause of pneumonia in Arizona, sometimes as frequently as two out of five patients. However, in reports from Arizona, primary care clinics test pneumonia patients for Valley fever only 2% to 13% of the time,1 emergency rooms only 2.8% of the time,2 and urgent care clinics only 2.0% of the time.3 Testing rates were similar in a report from California.4 Furthermore, a study by AzDHS found that 35% of Arizonans had never heard of Valley fever.5 This is important because persons who knew about Valley fever before developing illness were diagnosed sooner because they asked to be tested.

Lack of awareness about Valley fever has consequences. Before receiving their correct diagnosis, patients with Valley fever are often treated with antibiotics one or more times, receive repeated radiographic studies, and some patients even undergo biopsies or other invasive procedures.6,7 The CDC found that the average delay in Valley fever diagnosis was 30 days at a cost of $175 per day.8 Clearly, the first step in managing Valley fever is awareness of the problem exists in Arizona. Without that, long delays in diagnosis are going to continue.

This year, the University of Arizona and Banner Health celebrated the tenth year of their affiliation. This has allowed the VFCE to bring to Banner its expertise, and together they are addressing the lack of appropriate testing for Valley fever. A system-wide description of best practices was agreed upon by all of the Banner stakeholders. Over the past 5 years we have focused upon the Banner Urgent Care Service with training and ongoing review of the practice patterns in its many clinics. With attention to these details, the testing for pneumonia has risen from less than 2% to more than 20% in 20233 and more recently to 50%. From other findings, we found that an uncommon but distinctive skin rash, medically called erytherma nodosum and potentially caused by many different things, here in Arizona, was due to Valley fever in nearly two-thirds of the patients. This has led to testing all patients with erythema nodosum for Valley fever, just like those with pneumonia. Because of this VFCE-Banner partnership, awareness of this disease is growing within the practice and distinguishes it from other health care systems across the state. We are building a similar awareness of Valley fever within the 14 Banner emergency departments across the Arizona deserts. One of our members, Dr. Gondy Leroy, Professor in the UA Eller College of Management, recently was featured on NPR discussing other ways we are trying to improve early diagnosis of Valley fever.

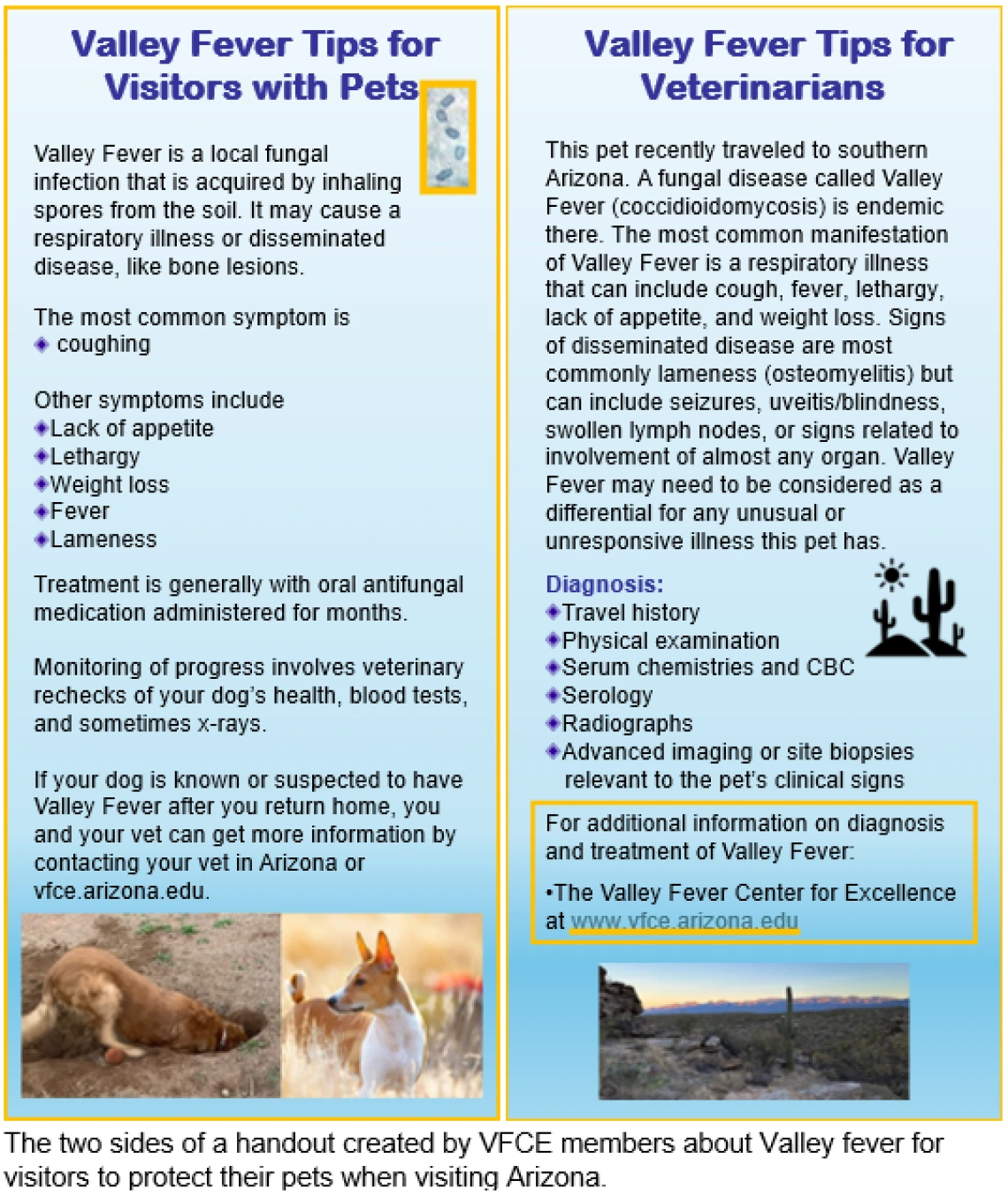

Because the general public needs to be aware of Valley fever also, the VFCE is spreading the word in the community. Athletes, like Michael Bates, a member of the UA athletic hall of fame, who have been personally impacted by Valley fever, have generously lent their voices to raise Valley fever awareness. Also, by coincidence, the Basenji Club of America’s 2025 National Specialty show is taking place in Tucson during Valley Fever Awareness Week. As part of that program, our lead veterinarian in the VFCE, Dr. Lisa Shubitz, will give a half hour presentation about Valley Fever. This talk will inform owners about the symptoms to be aware of in their dogs and the diagnosis and treatment of Valley Fever. Owners will receive a card to carry home with tips to remind them of the symptoms and to let their veterinarian know their dog could have been exposed to this common Arizona fungal disease if the dog becomes ill after returning home. Dr. Shubitz will also host a webinar, “Hard Facts and Heartache of Valley Fever in Dogs: Some science, stories and hope,” on November 12th that is open to the public.

If awareness is the first step and early diagnosis is the second step, then patients, whether people or pets, are in a position to receive the precisely tailored care for however serious their particular infection is. Fortunately, many persons have an illness that eventually resolves without any permanent damage. What they most need is the information and support to help them through what is often many weeks or months of symptoms. For a few people and more often in pets, however, infection becomes complicated. For those, defining the extent of disease and choosing the best treatment, which may include antifungal drugs and possibly surgery, is highly individualized. The VFCE is working with Banner to coordinate the various resources and expertise needed to patients with whatever Valley fever complications they might have.

Lastly, awareness of Valley fever leads to an appreciation of how we could do more for patients with innovation. For example, current diagnostics require blood or other specimens to be sent to an outside laboratory for testing and results take days or longer to come back. It would be so much better if a test could be done in the clinic or at the bedside with results within minutes and lead to immediate decisions regarding next steps. Also, none of the available drugs used to treat Valley fever cure the infection. This means that serious Valley fever infections must take these medicines for years, if not life-long. Awareness of this limitation leads to wanting that a curative treatment might be discovered. Finally, VFCE members have discovered a vaccine that seems very safe and very effective at preventing Valley fever.9 It has been licensed from the University of Arizona by Anivive Lifesciences, and development is close to producing a veterinary product to prevent Valley fever in dogs.10 Canine Valley fever is a very important economic problem for pet owners as recent VFCE studies have shown.11 Just as exciting, Anivive last year received a large contract from NIH to continue development of this vaccine as a product for humans. The value of such a preventative vaccine for Valley fever is only clearly understood by persons who are fully aware of how important preventing Valley fever would be for both humans and pets in Arizona. The VFCE has been able to contribute in all three of these areas, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention, for managing the Valley fever problem only because of the generosity and support of its community which benefits from these advances. A recent generous estate gift by Michael and Susi Harris of $2.4 million is gratefully accepted. With continued support from others, the Valley Fever Center for Excellence could do so much more.

Of the 23 years that the VFCE has sponsored the Valley Fever Awareness Week, I hope that this year that the “Awareness” takes on a special meaning as the key to managing Valley fever.

Cited References

1. Chang DC, Anderson S, Wannemuehler K, et al. Testing for coccidioidomycosis among patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Emerg Infect Dis. Jul 2008;14(7):1053–9. doi:10.3201/eid1407.070832

2. Khan MA, Brady S, Komatsu KK. Testing for coccidioidomycosis in emergency departments in Arizona. Med Mycol. Dec 8 2018;56(7):3. doi:10.1093/mmy/myx112

3. Galgiani JN, Lang A, Howard BJ, et al. Access to Urgent Care Practices Improves Understanding and Management of Endemic Coccidioidomycosis: Maricopa County, Arizona, 2018-2023. The American Journal of Medicine. 2024;137(10):951–957. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2024.04.028

4. Tartof SY, Benedict K, Xie F, et al. Testing for Coccidioidomycosis among Community-Acquired Pneumonia Patients, Southern California, USA(1). Emerg Infect Dis. Apr 2018;24(4):779–781. doi:10.3201/eid2404.161568

5. Tsang CA, Anderson SM, Imholte SB, et al. Enhanced surveillance of coccidioidomycosis, Arizona, USA, 2007-2008. Emerg Infect Dis. Nov 2010;16(11):1738–44. doi:10.3201/eid1611.100475

6. Donovan FM, Wightman P, Zong Y, et al. Delays in Coccidioidomycosis Diagnosis and Associated Healthcare Utilization, Tucson, Arizona, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. Sep 2019;25(9):1745–1747. doi:10.3201/eid2509.190023

7. Pu J, Donovan FM, Ellingson K, et al. Clinician Practice Patterns that Result in the Diagnosis of Coccidioidomycosis Before or During Hospitalization. Clin Infect Dis. Jun 8 2021;73(7):e1587–e1593. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa739

8. Benedict K, Massey J, Fearon Scales M, Hennessee I, Williams SL, Toda M. Impact of Delays in Diagnosis on Healthcare Costs Associated With Blastomycosis, Coccidioidomycosis, and Histoplasmosis in a Commercially Insured Population. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2025;12(8)doi:10.1093/ofid/ofaf499

9. Galgiani JN, Shubitz LF, Orbach MJ, et al. Vaccines to Prevent Coccidioidomycosis: A Gene-Deletion Mutant of Coccidioides Posadasii as a Viable Candidate for Human Trials. J Fungi (Basel). Aug 10 2022;8(8)doi:10.3390/jof8080838

10. Shubitz LF, Robb EJ, Powell DA, et al. Δcps1 vaccine protects dogs against experimentally induced coccidioidomycosis. Vaccine. 2021/10/23/ 2021;39(47):6894–901. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.10.029

11. Butkiewicz CD, Sykes JE, Camponuri SK, Weaver AK, Shubitz LF. The costs of the diagnosis and treatment of canine coccidioidomycosis in endemic regions, USA, 2022. Prev Vet Med. Dec 2025;245:106660. doi:10.1016/j.prevetmed.2025.106660